Sundance

This piece is a contribution to the STSC Symposium, a monthly set-theme collaboration between STSC writers. The topic for the upcoming issue is, at long last, Fiction. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed contributing to it.

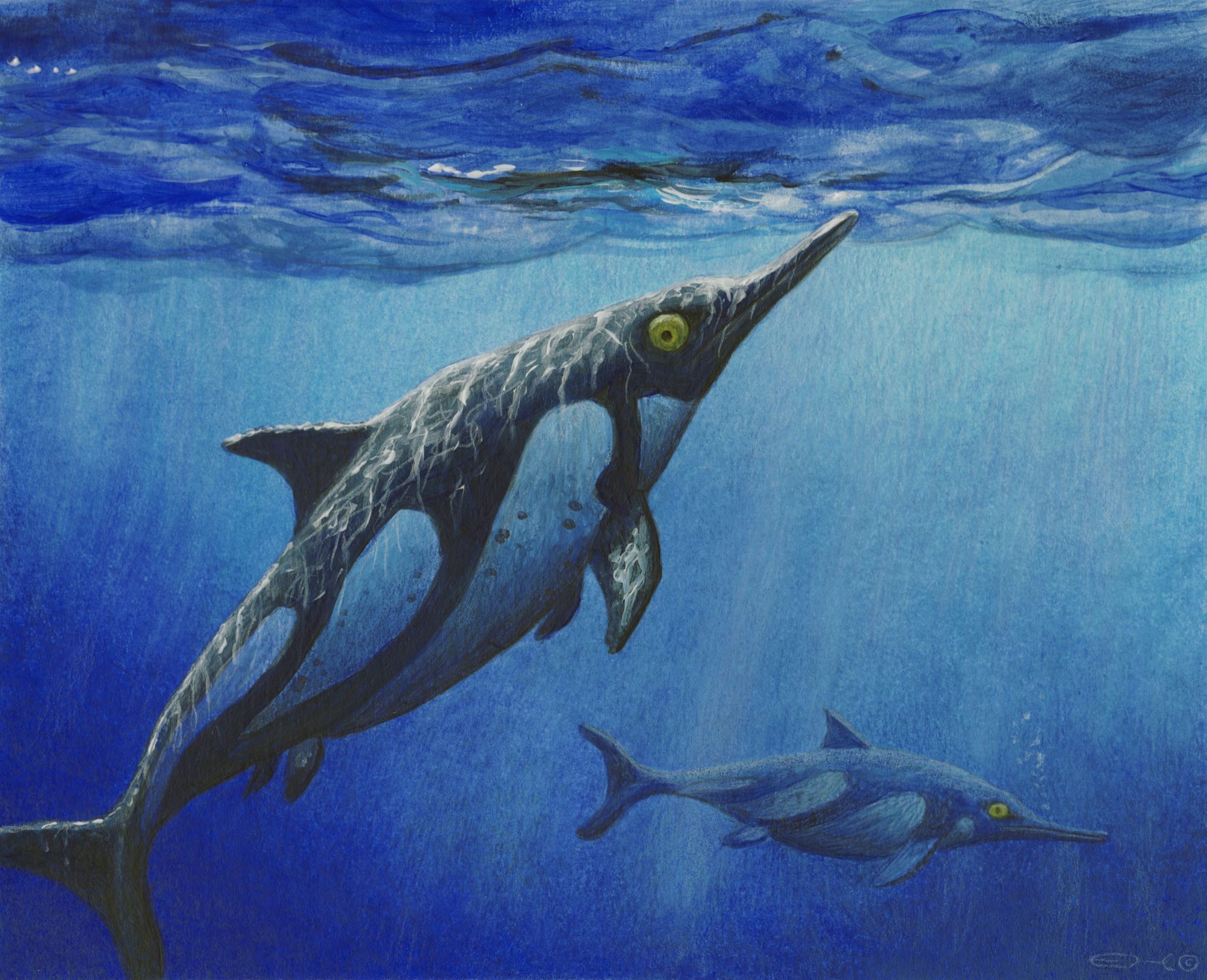

My deepest thanks goes to Esther van Hulsen. Check out the rest of her excellent catalog of wildlife art here.

The fish and megafauna had taught Reina by means both atrocious and commonplace the necessity of going deeper. Her children were learning quickly now that they were of age. The trio knew why she drilled them so, even if they had yet to fully appreciate the pressure behind her thinking: bygone supremacy buried in so much sediment, untold millions of years. They would soon. She made it clear that the kids—ophthalmosaurs as a genus, ichthyosaurs as a whole—had no other choice.

Reina’s tight quintet of marine reptiles was away from the shallows and a pinch less removed from other units of the herd, another day to be spent practicing in a patch of the inland Sundance Sea. After a few warm-up dives—straight down, slowly up to avoid the bends, Reina watching her charges closely—the core family parted ways with Uncle Euram, who was to again supervise the top of the diving column, guard for predators when the others came up for air. Euram was getting on in years, retired from active hunting duties, but he lent a flipper always to his kid brother’s only mate.

“Look at that fish school shimmer away,” Euram said, and hearing him Reina angrily hastened the kids’ descent. “Celso and I used to nab occithrissops day and night in waters like these. Smaller fish all around us, scores of ‘em, but we went big and outplayed them feckless plesiosaurs every time. The scapegraces thought those long necks of theirs would make up for a lack of brains. Pah! I remember Celso trounced one of ‘em so good…”

At depth came ever-increasing darkness, and Euram’s words were soon lost as gold sunbeams, petering out before they could pierce the sunken vale. Reina was grateful, not least for the fact that the kids’ aural faculties weren’t half as developed as her own. She didn’t blame Euram for reminiscing, but she’d told him over and again he couldn’t amuse himself so carelessly anymore. She now thought she’d been remiss to let him talk all along. At least the twins were alright; they had still grown up on squid alone.

The same couldn’t be said for little Nubar.

Soon all hints of the photic zone above the family vanished, the seas’ dark at flipper in an expanse of placid, richly pulsating void. The children scrambled on Reina’s mark. Nomi, who’d won the twins’ wager concerning who could breach higher en route to the dive spot, led the way into the blackness. As expected, she made the first catch. Reina watched her swim to Sever’s position and swank, a belemnite sideways in her slender jaws. She scarfed the squid down and replaced it with a toothy grin.

“Fifty breaches says you don’t find anything bigger than that, Sever,” she said. “Face it. You’re small fry.”

“Oh yeah, belemnite breath?” Sever, finding nothing of size in his vicinity, plunged deeper out of sight. “A hundred breaches! You’re on!”

Nomi gawked a moment, then turned up her snout. She redoubled her click-clack, croaking to the dark that Sever would be lucky to catch so much as paralarvae. Make it two hundred breaches. He wouldn’t find shark stool today!

Reina frowned. Nomi was the herd’s rising talent, praised for her prodigious hunting instinct and pedigree, her gracile features and fusiform build, that beautiful black-to-white speckled fell. But she begrudged the world its very existence, envied Sever even beating her out of the womb. The beak on that child, thought Reina. Buoyant brontosaurs.

Nomi might have returned to base and bragged similarly if she had time, but the kids were growing ever more. They needed the nourishment of several catches and all the practice they could get per breath of air, each of which afforded them six minutes now—five in Nubar’s case—with a buffer to be used if Euram spotted danger above. The kids didn’t always succeed with their prey, and the fewer times they had to ascend the better. Nomi and Nubar only worsened matters by hunting until the last second, then rocketing to the surface, to incur serious bone damage later on. Reina repeatedly chewed them out. The whole point was to survive. They had to feel the fact: such reckless tenacity, heady as it was, got a fine ophthalmosaur killed.

Reina oversaw all of her kids’ activities down low, suited to the task as her nine-inch eyes were. The trio flirted here and there with passing squads of their prey, driving targeted belemnites to jet their ink supplies into the medium and break formation, each handling the created nighttime in their own way. Nomi was brash, Sever methodical. Both snagged and ate a healthy few. Nubar struggled however, catching nothing, and in the heavy darkness he cried out.

“Beak up, Nubar!” Reina called. She swam over, unable to find him until he writhed out of an ink cloud and made to storm off. She quickly caught up, floated alongside. “What’s wrong?”

“Everything!” Nubar spat. “I can’t see in all that ink, and then I lose my squid. Every time!” He led Reina at a sullen, sluggish pace, not once reacting when food crossed his path. Reluctantly, for she expected much from her children, Reina snapped a squid from overhead and offered it to Nubar, who took it and turned away. She would have ordered him to watch her strike had she not done so many times before. It wasn’t that Nubar failed each and every dive, but Reina knew he had his limitations—those and a long way to go.

“I hate this,” he said, and Reina first thought he meant the taste of his meal and was mortified. “Sever and Nomi are bigger, stronger, and so much better at hunting than me.”

“Nubar, that’s not true.” Reina thrust ahead, halting them both. “Think about it. The twins are older than you. Of course they’re bigger. Of course they have better eyes. But they don’t catch every squid. Far from it! Nomi’s quite sloppy.” She drifted close and pecked him on the side. “You’re doing fine, hon. I have better eyes than anyone. You think I wouldn’t see that?”

Nubar shook his head.

“I wish I could see it.”

“You just have to keep trying, baby,” she said. “Getting ink in your face is a privilege, you know. It’s proof you make the belemnites shake in their shells. You’ll get the hang of it.”

Despite Reina’s encouragement, Nubar sighed and resumed his slow wander.

“Mama,” he said finally, turning about, “why didn’t we just eat the fish?”

Reina, who’d been studying Nubar’s flippers, confirming the front set was still longer than the back, froze.

“What fish?”

“The fish Uncle Euram saw. Why don’t we eat them like he used to? There were a lot of them, and they were right there.”

Reina took long to respond, in disbelief that her youngest had heard any of Euram’s earlier prattle.

“Nubar, your uncle exaggerates,” she said, which wasn’t untrue. “It’s like I’ve always told you. We’re better at catching what’s down here than anyone else.”

“But can’t we catch fish too? Sharks do it all the time.” Nubar shimmied from rostrum to tail flukes. “See? I’m almost as big as they are!”

“Doesn’t matter, Nubar. You keep away from the surface as much as you can.” Reina took her turn to sigh, bubbles and salt exiting her nares. “Even if there were enough fish to go around, I’d still forbid you three to hunt them. We let the sharks and plesiosaurs eat what they will. We are built unlike either of them, and we can do what they can’t. To not acknowledge that, now…?” She clacked her disapproval something fierce.

“Squid and squid only, I know. But Cambree, and others in the herd—”

“They’re wrong!” Reina shot. “I don’t care what you think your mother taught you!” Her facing eye remained fixed on her charge. “She might have fed you fish at the start, and maybe she took you hunting once, but I’m the one teaching you how to survive. Your mother didn’t know a thing about how dangerous this world is. I do, Nubar… Do as I say.”

“… Yes, Mama.”

With that, Nubar started swimming away.

“Nubar—”

Reina stayed herself and let him go, shivering. How she abhorred to see her little one down. She wanted to do more for Nubar, felt she needed to somehow. She had taken him into her care upon Cambree’s illness a few months back and didn’t dream of disgracing her dear sister again. She didn’t put up with failing anyone, living or dead, herself or a soul else, least of all the sweetheart whose mother had given Reina a shot of her own after she had been orphaned as well.

Reina wished to do something, anything. But she didn’t want to deprive Nubar of his duty to learn, nor did she want to suggest favoritism and risk neglecting the twins however much. She tried to strike a balance between her sympathies and the undying truth—the truth that would keep the kid alive. Nubar was precious to her, beyond. Full of his mother’s slight dimensions, her forward curiosity, her spunk. His adorable, searching eyes, also Cambree’s, were too cute at his age to do justice. But Reina hoped he would show signs of his father soon, coarsen and swell. Eyes yet larger than Cambree’s were a necessary adaptation for when the pelagic nocturne came calling, yawning forth in the course of destiny. In her youth, Reina had felt as if the deep were inviting her to the grave. Then she dove down there, putting to use her own spotless optics, and let it sink in how many of her kind perished in sunlight now. The reality still shook her, chilled her to the core. Her wide blue world had inverted from the tales of her shastasaur ancestors, even from those of the fearsome temnodontosaurs more recently, whom had prototyped the eyes for diving atop food chain’s peak. To Reina, ophthalmosaurs existed in this world to mount a response to it, like any fortunate animal. She didn’t think the idea had been taken seriously enough. She wished she had more help than rickety old Euram, but alas. Someone had to lead the way.

The scars on her face briefly burned anew.

Reina idled a trice to see Nubar off. Though she could see the glimmers of motion for hundreds of meters around, his smooth, majority-dark hide blent quickly into the surrounding deep. He had the white underbelly necessary for countershading, camouflage from above and beneath like any other ophthalmosaur, but Reina was ever grateful the kids could train freely down here and out of harm’s way. Once Sever, Nomi, and Nubar too left her to join hunting groups—Great One willing—they’d find themselves doing what she’d done nightly into her years as a young adult, the work she’d undertaken when in the course of events she grew smitten with Celso, the twin’s father: storming belemnite shoals at the surface when they rose to feed on fish larvae, ten ophthalmosaurs or fewer slashing from below into squid several thousand strong, spiking individual prey on dense teeth rows. Reina swore the ink jets from those days before motherhood still clouded her brain. But to grow and sustain her eventual two-ton, twenty-foot frame, she had hunted ceaselessly, taken the risks that informed her dire outlook. Swooping pterosaurs wanted in on the surface action and could catch the smaller ophthalmosaurs—not Reina!—if the latter weren’t careful. Worse, the feeding tended to blind her kind to anyone shadowing them in the water. The competition provided by plesiosaurs, whom with their long necks and strong paddles could speed and swivel and snipe small fish with ease, had been one thing. The advent of newer marine reptiles, names of whom spooked ophthalmosaur children and adults alike, had been quite something else.

After ensuring Nubar was hunting in a fertile patch of deep, Reina again checked on the twins, thankful they had been occupied. Nomi kept at her headstrong antics, slicing and dicing water sans regard for the ink in her way. She would have to spot prey in microseconds eventually, what with each belemnite’s speed and size, swivel her jaws to take it instead of turning her entire body as well. Sever, meanwhile, who was more precise but too much so at times to execute, had slowed his pace, actually stopped hunting entirely. His outline hovered low in the murk. As with her youngest, Reina swam over to Sever, perching above.

“What’s up, sweetie?” she said. “Time’s clicking!”

“Oh, Mom! Sorry! Just a sec.”

Sever seemed fixated on something, nothing dietary visible in his beak. Reina dove to his side.

“Don’t tell me you’re okay with losing another bet to Nomi. I won’t abide that.”

“I’ll win this time, Mom. Don’t worry,” Sever said. “Just thinking is all.”

“Oh? What about?” Reina beamed in secret. Sever took after his father in looks, his mother in optic size, yellow orb erupting from black on each side of his face, and likewise he possessed the combination of Reina’s wits and Celso’s rare form. He could become a top historian, an ace diving instructor, a devastating hunter, all of the above if he so chose. Reina tried not to press him on any one vocation, only desired he find a passion among his strengths and pursue it soon enough, make up his mind. Whatever his case, Reina thought Sever the perfect package just about. She hoped he would take most to inheriting her mantle after she was done.

“Sis was saying stuff about how I’d find nothing down here,” Sever said. “She already checked, I might as well give up now—that kind of flotsam. But she’s wrong, Mom. She’s so incredibly wrong.” He swiveled his small head and gargantuan gaze, drifting over a vast plain of sand that stretched forever in the dimness. Reina dropped all the way down. The seabed was motley and dense, flush with the forestry of stalked crinoids, with urchins, starfish, and bivalves.

“I’ve been too focused on catching any old squid to notice,” Sever continued, “but now I see new things everywhere I look.”

A squad of belemnites approached and shot wide of the pair, ten arms apiece in trail, drawing Reina’s attention to the shadows of other cephalopods, the hard-shelled ammonites, proceeding more slowly in the blackness around.

“It is pretty, isn’t it?” Reina said, if only to not leave Sever hanging. She thought him more than a bit distracted in stopping to smell the sea lilies this moment and thanked her daughter insincerely for making him mess around. The kids were soon to ascend for air.

Stirring Reina from her thoughts then was Nubar, the tyke speeding overhead and into her blind spot.

“Good, Nubar. Go slow now!” Reina called, angling to see him rise. “Keep at it when you get back!”

Nubar didn’t reply, though Reina expected as much. Of the kids he had the least lung capacity, not half as much breath training in the short time he’d been with her. He needed the rest of his air to climb and take in more.

With eyes capable of independent motion, Reina had kept one vigilant while visiting with Sever and watched Nubar practice, listened to his frustrations, counted the gushes of ink. She was proud of him for managing as much as he did—fish, after all, weren’t quite so tricky to learn. She was also pleased he had timed his ascent safely for once. There was nothing wrong with not catching any squid, nor with being first to go up, she told herself, so long as the twins didn’t judge. So long as Nomi didn’t judge. Reina would stuff her mouth with silt.

“Mom,” Sever said, jerking her back.

“What is it, sweetie?”

“You told us before that our ancestors swam in the open ocean. It’s deep there, right?”

“Yes, Sever, it is.”

“Did others of our kind reach the seabed when they were alive too?”

Reina glanced at the open plain and swam off, trying to conceal her annoyance.

“No, dear,” she said. “Not a one.”

Bubbles passed audibly from Sever’s nares. “… Wow.”

Sever next indicated he should surface, redeeming himself a bit, and Reina persuaded him to make one last catch before going up. Under his mother’s watch, he took no time at all to locate a relative behemoth of a morsel, only seconds more to secure it. He told her he could taste victory, let alone the savory sweet of squid guts. Sever began his ascent, and Reina went over to Nomi and insisted she surface too or else.

“Or else what, Mom?”

“Honey… you don’t want to find out.”

“Whatever.”

Nomi then saw the catch in Sever’s beak and tore after him, fuming.

“Go slow!” Reina bellowed. She wondered which would go first, her kids’ bad habits or her larynx.

Reina herself had another ten minutes left in the tank, so she waited below, organizing thoughts, catching squid of her own now that she was free. She looked forward to hearing just how many thousands of breaches Sever would get out of Nomi by session’s end, how Euram would educate her on placing wiser bets. Nomi would sass him till morn. Regardless of age and how much Reina openly despised the fact, the two of them sure liked to talk. Nomi might retire too someday and boast of her time leading a hunting group like her father, even if she did only eat squid. The genus case for sexual dimorphism certainly favored her ambitions. It made space for embryos, true, but on females it bestowed size overall as well. Reina worked closely with Nomi to develop her tail muscles, the only ones shortened by her genes. Today’s breach-gambling would do nicely in that regard.

“Mom!”

Reina snapped to attention. Two minutes had passed; now Sever and Nomi returned together, racing to her in a spirit that was anything but competitive. It only took her laying an eye on the twins, seeing them reappear first, to sense the problem, have maternal instinct send the contents of her stomach, the squid she’d just eaten, well into her throat.

“Mom! Mom!” Nomi yelped. “Nubar’s gone!”

Sever nodded apace. “Uncle Euram said he never came up.”

Reina took a wild look around. All about the demersal zone, then down at the benthos: nothing. She couldn’t believe it. Nubar was tiny but still a good seven feet long. Where had he gotten off to? He might have been the youngest, the least experienced also, but he wasn’t stupid.

Right?

“Where’s your uncle now?”

“At the top still,” Sever replied.

She glanced up. No doubt Euram had sent for her.

“… Okay.”

Reina quickly gave the twins their instructions, bade them keep hunting and stay put. Come up for air, of course, but stick to the deep. Don’t leave the diving column unless your life depends on it. Understood? She didn’t care that they knew the drill or that they’d heard it from her a thousand times. They’d hear it again when next she had no better choice but to let them out of her sight.

She rose from the deep faster than was desirable, anxiety burgeoning, concern for her body’s gas buildup null. Halfway up, she began to see spiny-finned hybodus sharks massing around the top of the diving column, skirting Euram as the belemnites down low had Sever and herself. The sharks were deft, versatile predators, but they only ever reached the current size of the twins—less than half the size of Reina—and had been mere pests the time when, bobbing at the surface for minutes on end, she had strenuously given birth, her adoptive mother present to ward them off. Here and now they swam without nerves, however, drawn by the red spark of wounds welling in the brine. Reina could smell it too. The scent called out to her over sundry others, redolent of all she’d forsaken in service to her kin, and sent her aquiver beak to back end, shooting for air. She breached near Euram and plunged back trying not to lose her mind.

The adult ophthalmosaurs met eyes and moved close to one another, flipper brushing side in silence, doing as the species was wont to do when the feelings ran high.

“Protect them, Euram,” she said. “I’m counting on you.”

Euram assented shortly, his facing eye grave.

“And I you, Reina… Great One be with.”

It was custom to reciprocate such a petition, but Reina found she could only tear away with an awful whine. She sped for the sharks’ attractor, driving her flukes with abandon and praying to save her soul. Nubar had said he could catch a fish as well as a shark can. Had he really dodged Euram somehow and gone and tried it? Why? Reina prayed to every ancestor that she wasn’t too late and her little one was still alive, apologized once more to Cambree and begged to know that if anything were the case she watched over him still. The sharks couldn’t much harm Nubar one-on-one, but the situation was akin to a nightly feast of squid. So many bodies in one place, the feeding could turn to frenzy. The odds of catastrophe, of inviting it then, were nigh guaranteed.

Eventually Reina reached the remnants of the school of fish Euram had first seen, and through a screen of lesser sharks she made out the ongoing stage of mess: fish bolting, the hybodus reduced to heedless fury from the inside out. Sunlight speckled a spinning globe of gore. Then, as if having listened to the worst of Reina’s worries, a twenty-foot pantosaur, the largest long-necked plesiosaur in Sundance, hurtled into the meal’s uppermost reach, slender collum on stout body with four flippers sifting through the sharks, fish collected in compact jaws. Reina glanced at the gorging reptile atremble, watched it spread the melee, displace and disperse the myriad swimmers. The bait ball bent, rolled and roiled, reforming on itself, yet with her vision Reina was still able to pierce its density. In the wake of the pantosaur swam another soul out of place, looking and darting, this way and that. It was little Nubar, and he was unscathed, though he had more with which to leave Reina stunned. He targeted an errant fish to his left several body lengths off and shot for it, missing but cutting teeth into its scales. He shifted to slash again, red wisping into the medium. A shark dipped across then and took away the kill. Others came, their frenzy converging on the spot, and Nubar swam back.

Reina, her wits dead to her and her body inexplicably taut, had expected him at that moment to give up, give in, come back to good sense. But she saw a fervor in his eyes, saw him scanning again, saw him find a fish and lock on, and at once she wanted to say so many things to the child, overcome. As he cut for his prey, Reina charged after him, and likewise a single large hybodus zagged among the other carnivores in Reina’s periphery. Havoc if the interloper collided with Nubar en route to the prey, stabbed him with its fin spines and woke the instincts of brethren nearby. Though far from Nubar, she turned and thrust at full power, intercepted and hit the hybodus broadside in the mouth. She sent it careening, bleeding back into the fold, and turned her attention to Nubar before diagnosing its fate. Her child hadn’t noticed her. He had his target secured in his mouth.

Above and behind, Reina saw the sunbeams shiver, silhouette of pantosaur returning to make a second sweep. Any vestige of awe left her outright. The plesiosaur had yet to begin passage when Reina bolted for Nubar, clearing sharks, and shrieked at the top of her lungs, her whistle breaking halfway through. She had many things to say, but among them only one mattered here and now.

“Dive, Nubar! Dive!”

Her son flinched. He slurped his catch upon spotting her, looking like he might flee in fear of punishment above all else.

Gallons of blood had stirred the water. No animal alive was safe.

Reina started to repeat herself when a wayward shark thumped off her, but briefly obstructing her vision. But briefly was long enough. There was a steep crag not far from the feeding off in Nubar’s direction, and oblivion took the form of a full-grown megalneusaur bursting past its towering peak. Four colossal paddles, all head and no neck and five feet of crooked teeth sheared through the pantosaur, a distant relative the dread pliosaur took by the throat and brutally crashed above water. Fish and sharks scattered to the current, carnage yet crackling in their occasional miniatures, the bait ball gone. Reina kept going, kept screeching, and at last Nubar broke for the dark, likely spurred by sight of danger, genetic memory telling him to get. The titans came down trailing fresh, frothing chaos, pantosaur chunks torn loose as a thirty-foot, ten-ton apex predator put its prey through a death roll, savagely spiraling in the depths. At the maneuver’s closest to the ophthalmosaurs, between rips and shreds of the pantosaur’s torso, the megalneusaur roared. Fine, thought Reina. It could cry after them all it wanted. Even if it changed cravings right away, she knew both ophthalmosaurs could lose it down low.

The predator’s roar echoed.

Then she saw the second one.

The younger, smaller megalneusaur—one that was still her size—was coming too fast for Reina to think, on a direct course for Nubar from someplace she didn’t know. Around the crag, out of the black, out of the blue. Somewhere out of its parent’s shadow, signaled just when to strike. Reina whimpered. Nubar’s raw speed had quietly impressed her this horrid day, but she knew beyond measure that her little one couldn’t save himself now. The years flooded back to her then, all of their pain. She crash-dove at top speed.

“Nubar!”

The megalneusaur’s maw gapped for her youngest, a darkness to end lineages, erase entire histories—

“Dive!”

—and Reina, arcing, slammed into it from below.

The impact cracked her upper back, where vertebrae bunched by evolution to avoid gas pockets had provided her only means with which to ram. Reina’s vision flashed white; the sea rocked. Harsh ringing scourged her inner ears. She swallowed water involuntarily and was briefly set adrift. Then, as perception began to return to her, she felt fangs colder than life tear at her leftmost side, agony light up her world. She squealed through gritted teeth, despite herself able to keep out the brine. Adrenaline flooded her system, nerving every last muscle. The junior megalneusaur could attempt to shake her apart any moment, could smartly release and bite down again to get a fuller grip. Maybe it would even mangle her extra for daring to deprive it of food. Whatever the case, Reina’s simple will to survive told her now or never and sprung a violent full-body twitch, wrenching her free and off into water. Immediately she righted herself and bolted. She was terrified, almost out of air. Still, she swam at an angle to the surface, skewing horizontal. Her muscles blazed the more her oxygen was stretched, and one or both of the pliosaurs were in furious pursuit. They likely gained on her for a span—her ears were still ringing and she could scarcely look back—but through and through their ilk were ambush predators, ill-suited to chases. She knew her cruising speed would outstrip them given she swam a long straight line.

With distance the seabed soared to meet her, climbing ever closer to the tips of her flippers, and soon Reina plowed into the first shallows she could find, to be absolutely safe. Her first thought was how she’d go about returning to Euram and the kids, confirming that Nubar had made it back. Coasting, she turned and slid laterally up the high sand, high enough that her head came above water and she gasped. Finally. Sweet air scurried in.

Crushing pain stabbed her in the chest.

Reina hissed, hurting only more, panicking. She fought herself down by degrees and lay there in the gentle surf. The pain ebbed just a bit. She hoped adrenaline had given way to the din of her injuries and took another, deeper breath, only to squeal, squirm, remain there on her side, sobbing into the breach. It took a supreme effort for her to quiet down and again respire gingerly, to not attract terrestrial carnivores nor pterosaurs on the wing with her noise. No, she thought, this wasn’t happening. It couldn’t be. Not to Reina. No. She had promised them so much. She wasn’t finished. She’d barely started! There was so much work to do!

She had said she’d always be there for them…

Surf caressing her, shaking, Reina slowly permitted herself to pule. She resolved to focus as best she could on the sights around her, like air take them in and love them with her selfish gaze, for right now she needed such an unstinting salve. The great dome of the blue above her own consumed her facing eye, filled it with sun—the bright, all-seeing orb of the Great One, ichthyosaur of legend swimming sky—and bright clouds and large harpactognathi flying in their cast. Below these went the westward sea and floodplains to the east, low green land radiating from beach that in turn was born to hydrous infinity. Empty shells cluttered the sand around her head, prompted commiseration she gladly gave. Not far offshore, there came an angry splash, jaws parting water and resting ajar. Reina giggled brokenly at the young megalneusaur, the idea that it had surfaced here to mock her, magically knowing of her fate. It left soon after, but still she laughed, thankful for its presence, thankful to all. Every sense and observation served to filter the feelings she only wished to scream. They each helped her through her heartbreak, the tender and sudden shock. Reina hadn’t beached herself, no. But a shredded left flank, a punctured left lung. She could feel the damage, and the realization had collapsed her soul. So Reina breathed slow and took it all in, for a short time insatiable.

She really was going to die.

The greatest part of her sadness was that she’d broken the promise she made to her children and to her sister and to her kind, that she had vowed her presence through to the end and could no longer keep her word. She’d told the twins as much when they had been just a few weeks old, pledged the same to her ancestors under the night stars. She had reaffirmed herself to all after the presumed death of her mate. Reina had taken Sever and Nomi to safer waters than those Euram had returned from after the incident, Euram letting out on his own, unusually concise terms that they’d lost his kid brother to a pliosaur at sea. To the end, Celso had done what he enjoyed most, making havoc of fish bodies and squid arms and ink surges in far waters beside his elder brother, for a time too with his future mate. Celso had been part of Reina’s every darling memory; Euram said he couldn’t have asked for a better life. Reina came undone, devastated despite Euram’s efforts to keep her afloat, knowing she had loved and lost Celso and at the same time putting two and two together. She figured out that the life they’d led together was one to be lead by fools.

Reina and Cambree, before sisterhood, were half-sisters by a common father. He had done as usual in mating with a different female each year, kept at it longer than most in his quest for sons to hunt with him in distant seas. He died unsuccessful in his endeavors, only siring females to the day a giant’s jaws came to claim his flesh and bones. Reina later heard from Cambree’s mother, who was ever the font of knowledge, that his firstborn son had been eaten by a rogue plesiosaur who found his herd’s nursery on the continental shelf. In having no heirs to his prized hunting group—all of which were same-sex, the rowdy males swimming wider ranges while females anchored close to home—he had rued his lot to no end. Reina felt sorry for her father, as often as he’d been abroad and away from her life, and from his tragedy she tried to learn everything she could. Upon birthing the twins, she’d thought he might be pleased to know she had a son.

It was Celso’s death, an echo of her father’s fate that would forever be brutally unfair to her, that told Reina to adapt. From then on, Reina had trained her offspring to master their charge, hoping they would live out full, sage lives in the splendor and bounty of Sundance, ever struggling with the fact that their father’s sense of adventure coursed in their veins. But Reina was lucky, blessed with life by Cambree’s mother, and she knew it was unacceptable if she didn’t give her all to ready them for the inveterate ways of the world. She knew full well Nubar’s upbringing posed a lethal risk to him and had adopted him in spite of it, knowing his grandmother was too feeble to raise him alone. Cambree had thought Reina’s abstinence from ocean and fish alike after Celso’s death extreme, reckless, and fought with her over the twins’ welfare. She eventually refused to speak to Reina until the sickness took her, after Cambree’s mother had told her to give it up. Before that, however, one late evening when Reina had left the twins breaching with Uncle Euram to fetch herself more food, a party of males she wasn’t acquainted with stormed her in the far shallows. Most males formed and remained in hunting groups for life, but they did return to mate, and some among them served as patrols for the herd in that time, in place of the maturing and retired who usually swam vigil. The trio of males attacked, and Reina parried, snouts clashing and trying to bite down. Lacking bladed teeth, the ophthalmosaurs fought by clamping each other, attempting to wound, break bone, or blind. Reina was much too strong at this point, however, and she took half the sight of a smaller male after a harrowing struggle, during which the largest male had pressed down on her dorsum, perhaps trying to drown her by keeping her from air. After blinding the little male attacking her face and shaking off the big one, the patrol deserted her, left her gasping at the surface and bloody near the eyes. She waited before returning to her family, explaining to the kids that another ophthalmosaur had gotten feisty with her over a particularly juicy squid. Reina couldn’t see the reason for the attack right away, but after confiding in Euram she realized the truth. The incident prompted Euram to double down on protecting the family, using his influence on the herd without hesitation to expel the offending males. Cambree’s spite, the attempt to relieve Reina of her charges by deadly means, remained private, however. Against her sister, the battle-tested, severally scarred mother took no action. She only sought to understand what she had done to make her first friend hate her so.

Reina didn’t know how hard their father’s death had hit her sister, but at the time, and before her last year, Cambree had never had a mate. What Reina had been through she didn’t understand. She’d never swam and hunted with her love, much less lost him to carnage, even as she would reckon with as much in time, shortly after Nubar came to be. Growing up, Reina had been the quiet one, aloof and weak-willed. Cambree had been instrumental in opening her to the world. She had her sister to thank for bringing her one night to listen to Euram, the herd’s foremost storyteller fresh from an excursion, who then at length introduced her to Celso, who was agile, daring, and shy as a clam. Reina and Celso had proceeded to open each other, mavericks in search of fun under the sun, who defied hunting-party wisdom and went cackling together into the fray—Euram along to lead a selection of other males for support, let the rascals know exactly who Reina claimed. With Celso gone, Reina saw her experiences as why she’d come to both love and despise life, but none of her adventures would have been possible had Cambree not been there at the start. Reina forgave her sister, apologized many times over. Reina never held Cambree’s feelings against her. Though she considered adopting Nubar both self-sacrifice and a high revenge, she knew her thinking was petty at best, knew she would have raised Nubar regardless because of everything Cambree had given her before. Her sister simply hadn’t known. Hadn’t known her pain, her happiness, nor the fullness of her gratitude, had passed away before the darling ever could. With this Reina lived bitterly, with what she saw as the consequences of her convictions, blaming herself for alienating Cambree in doing what she thought was right. She had come to terms with her decisions. But in the end, even now, she wished she could have heard her words repeated back to her, before Cambree died.

Reina had determined to always be there for the kids, watching them grow, seeing them off and no matter how painfully-joyously welcoming them home, privy to their exploits and those of their children too. She wanted for Sever, Nomi, and Nubar what her parents had been unable to do for her, after father met his dismal end and her true mother—who grieved, took another mate—died from infection, a stillborn stuck in her birth canal. Reina vowed not to make her parents’ mistakes, nor those in her past, ranging at Sundance, feeding in darkness, giving birth to one set of young. She knew no one around her had chosen death, but she took the habits that had taken her loved ones to die in the depths themselves. Playing things wisely, Reina had thought she could make good on her goals, thought she could witness her children make good on theirs. She had expected to do right by her family and by her kind, to repay the charity shown her a thousandfold. After raising her children right, Reina had wanted to teach the rest of the herd to cut a new niche, to shift their course and prevent what by the teeth of the pliosaurs could become their extinction. She had hoped to see her life’s work through to completion, to leave things comfortably in the flippers of her children once she was done.

But this was it, wasn’t it?

There came another trying increase in her sobs; frustration quickly followed. Her kind had come so far in their time upon this blue planet, reigned over its oceans and ever-shifting waterways for so many lavish epochs. Reina had observed at times in her life her evolution failing her—being outpaced by fast teleost fish, being outmaneuvered by the sharks and plesiosaurs who snagged those fish, crash-diving at the merest hint of a pliosaur—and always wished it not to, always trusted that her ancestors had found a way. Why had her body failed her now? Reina rued her inability to fight the young megalneusaur, that her head was too small and her snout not blunt enough to charge the creature without either smashing apart on its too-tough bulk. She regretted not having the teeth to skewer it like it had her, wanted her kind to still top existence so she could have grown to fifty feet and eaten the ink-stain whole. She slapped her tail on the sandy bottom. Her weakness as an ophthalmosaur had cost her everything. She couldn’t fathom not being pissed.

But such thinking was a waste of her last breaths, she knew.

Altogether, Reina waited a time before haling herself back to sea, careful breathing but hurried all the same. The earth and skies were majestic, but the water was equally timeless. The sea was the abode of her beautiful kind. Predators might soon have spotted her, even if she was quiet. She wasn’t about to let them keep her from knowing her children were safe.

Reina traveled shallows along the lip of the sea, scattering small fish and crustaceans. She didn’t eat, didn’t wish to disturb other life. A blood trail twisted behind her, trickling and vanishing, but no self-respecting pliosaur of Sundance dared risk beaching itself for bait. She worked her way to a nearby armlet whose bottom trenched and briefly thought of swimming its floor out to the diving column, really wanted to, ultimately decided against. She was a ripe lure at sea, and no matter how she rejoined her family, surfacing with them en route to the herd was begging for tragedy. Instead, Reina continued along the shoreline, the long way, twitch by twitch of the muscles in her aching, staggering tail. Nothing bothered her save for steady pain.

Eventually she slogged into the vicinity of the ophthalmosaur herd. There, Reina cried above water and was fast met by a patrol. The young males escorted her to safety, still away from the herd so as not to draw a pliosaur to everyone, and into the care of a close few friends, fellow matriarchs of their fold. Reina thanked the males profusely, then requested that they go out to Euram and the kids, tell them she was back home and would await them in the cove nearby. She explained nothing of what had happened to her, barely able to sound out her wish as it was over the wound in her heart. Each ophthalmosaur present nodded, and a rescue platoon set out at once. Her friends—curious allies who in recent months had come to see Reina’s drilling of her children for themselves, those she had hoped to instruct first once upon a time—quietly helped her to her chosen spot, then let her be. Whether she was solemn or all toothy smiles, when Reina, sole mate of Celso the Dauntless, mother of the twins, and bearer of such scars as decorated her rostrum spoke, the Sundance herd listened. Her silence parted continents.

It wasn’t terribly long before her family entered the cove, the kids at keening upon seeing her in the flesh. The twins rushed Reina and nuzzled her, she them, and Nubar, Euram shadowing, brought up the rear. The eyes of her youngest were haunted. Reina watched him hesitate, look back to his uncle. Euram nudged him forward with ire in his thrust, and the tyke closed the gap to her in a heartbeat, joining his siblings, blubbering at once.

The kids were in the process of rounding Reina when Nomi discovered the hole in her side. Her daughter pulled back.

“Mom, you’re bleeding bad!”

Reina nodded gingerly; Sever went to inspect. Each of the kids then looked about the darkish water in which they had surfaced and grew scared. Reina’s heart clenched. She hadn’t had composure enough to warn them in advance, though even if she had, she doubted her words could have prepared them at all.

Suddenly Nomi turned on Nubar and snapped at his snout, missed. She bit again, then smacked him across the face with her flukes, water popping airborne.

“Nomi!” Reina cried.

Nubar bawled, cowering from Nomi’s aggression. She lunged for him, only to herself be tossed in the surf as Euram crashed between them. Nomi snarled.

“I hate you, Nubar, hate you!” she said, trying in vain to get at him still. “Why’d you have to come into this family?”

“Nomi, that’s quite enough.”

“No, Uncle Euram! It’s all Nubar’s fault! Mom got hurt because of him!”

“I’m sorry!” Nubar wailed. The little one melted into sobs and quickly submerged his noise in the water.

Nomi didn’t relent. “Sorry doesn’t cut it, dummy! It never will! I wish one of those pliosaurs got you and—”

“Nomi!”

The shriek ripped through the cove. Everyone turned to Reina, who hadn’t moved and indeed trembled where she perched, hurting from her outburst.

“Stop, Nomi…” she whispered, staring at the remains of her family in utter disbelief and shaking her head. “Please… Not like this…”

Euram’s stern expression broke in front of her, replaced by a fast glance of shock. He appeared to get her meaning and swam round so that he faced Nomi hovering at Nubar’s left, his rugged features vitalized by a tumult boiling inside him, threatening to make him burst.

“Apologize,” he said. “Now.”

Nomi shot an eye to Sever for backup. “Why should I apologize? Nubar’s the reason Mom’s bleeding right now!”

Euram grunted, lightly rocking the water, nothing else telling what he might do.

“Because, Nomi,” Reina breathed, sparing her and giving at last into deep and open sobs. “Nothing can be done about that. I’m going to be leaving soon… I’m sorry, honey… I’m sorry that I can’t go on… Don’t let this be the last thing I see…”

Nomi faltered, looking around at the stricken family. Sever beside his mother huddled up to her side, minding the gouge higher on the same flank. He whimpered, muttered protests to the revelation she had just shared. Such was all he seemed able to do.

Nomi turned again to Nubar, growling low and slow above the water.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and she went over to Reina. They touched beaks with a clatter, and Nomi gradually took a place at her mother’s side.

Her daughter taken care of, all they would get out of her gotten, Reina nodded last to her youngest.

“Nubar,” she said. She nodded again. “Come here.”

The child only shivered in place.

“Go on, Nubar,” said Euram. “Nomi won’t do a thing.”

Nubar started swimming, eyes divided between mother and sister. He came inchmeal, shaking his head as he went.

“I’m sorry, Mama,” he said. “I shouldn’t have gone after the fish. I should’ve listened to you. Please don’t die!”

“Nubar…” Reina cooed. She lifted her head, and Nubar submerged, burying himself underneath. The twins brushed her in turn, and Reina agreed—it wasn’t fair. Her feelings wanted to overflow. Still, she had to be strong, and instead she tried looking around the cove. It wasn’t much, but another shallow breaking against the scarp of a wide spot of highland, a thin forest at the edges complete with a narrow beach. Such a setting wouldn’t be her final resting place, she thought, but for now it would have to do.

Reina didn’t ask Nubar to explain himself. She affirmed her presence to the twins at her sides, let them know they were loved, and let him sob his piece. His reasons were easy to guess and hard to stomach, she knew now, and she trusted Euram to set him harshly straight when everything was said and done, this among the many other things she would discuss with him shortly. What mattered to Reina was that Nubar had said, was still saying, that he should have listened to her, that he should have listened all this time. His babble went a long way in soothing her heart, however sapped and mangled her heart continued to be.

“It’s okay, Nubar,” she said, and lay her rostrum over his back. “I forgive you.”

Nubar quietly made his noises.

Reina quietly let him.

At this point Euram took over, as Reina had expected and as she had hoped. He came up and nuzzled with her too, showed no desire to stop. Then he faced her offspring together.

“Alright, kids,” he said. “Let’s make a circle.”

“Yeah,” Sever said after a gulp. He looked at his siblings and tried leading them to positions. Nubar refused.

“No!” he yelped. “I don’t want to! I don’t want Mama to go!”

Nomi splashed him with her tail. “Nubar, you dummy, we have to.”

He pulled back and shook himself vigorously. “No!”

“Sis is right, bro. It’s tradition,” said Sever. “Come on.”

Nubar pled with Reina, his eyes trembling.

“Please, make a circle with your family, Nubar,” she said. “Do it for your mother.”

He nodded, gaping tensely.

The members of the family each circled up, then swam round Reina slow and gentle, equidistant from one another, snouts just above water. Nubar was stiff. Reina stared at the sky and listened, her periphery fading. The sough of her family’s wake filled her, washed and cleansed her, like the voice of eternity. She let it expand and envelop her, carry her to a place where she was lost in the luster of noontide, when the bright orb that presided over all history was at its crest, the Great One swathing life in light at the height of its breach. Tradition had it for ophthalmosaurs to ring the afflicted, the ill and dying and even dead, to grieve and love them and mark their passage into the next, to also express solidarity of faith. The Sundance Sea had been named for the movements of Reina’s kin, their observance of the star which had patiently observed them and their ancestors before them and all of their vaunted past. They danced for the Great One to watch over their deceased, to watch over their living as onward they swam. Reina had many times participated in the circles, which often formed without a body but around the idea of one, or loved ones if they could be found. She hadn’t been old enough to appreciate them for a while, then starting with her father had experienced them as something closer to what they were. She had wondered what it was like to be on the inside, that much nearer the center, the eye, the source. She sensed there wasn’t really a difference. It was a matter of age, wisdom, heart, rather, that permitted sun dances to fill a sensitive soul with interconnection and calm. Heavy as Reina’s chest was, painful as her form and feelings might be, whether she was living or dying or Reina at all, she felt alive, here, with hers. She felt the eons looking down as she looked up, knew her kind would be provided for as much as they persevered. There was nothing more to ask. There was nothing else she needed to know.

Briefly, Reina looked back on her resentment for the weakness that had been hers. The shonisaurs, shastasaurs, and thalattoarchons had each deemed it a privilege to be apex predators in their days alive—good on the pliosaurs for taking control, concluded the noble sentiment embedded deepest in Reina’s genes. Her spirit laughed, feared to consider what the late temnodontosaurs, those she owed for her greatest strengths, might think of her taking her bauplan for granted at the tail end. She thought of her parents similarly, and of Celso too. She laughed and apologized to each and all. She had been a fool as well.

Ichthyosaurs had never been without their weaknesses. Though the stories were often muddled and marred by extinction events and myriad faunal turnover, as far back as genetic memories went the kind had been around since the dawn, when the eye of a great ichthyosaur first trawled the blue sky. The temnodontosaurs, for example, had not been lost to time, as the ammonite-eaters among them had survived an extinction event to tell the tale, how the apex species died out from the depletion of their prey. The survivors had grown large before then to gulp more oxygen and hunt differently deeper down. Reina had taken their success as hard evidence her convictions had merit, that the ophthalmosaurs could live as mesopredators until such time came that they could evolve and reclaim the role of apex hunters, but she had to acknowledge that other ichthyosaur genera had later watched the ammonite-eaters disappear too. These temnodontosaurs had lived out of sight in the darker oceans, so their reason for vanishing wasn’t quite clear. Still, Reina knew whatever killed them off had been a fatal flaw indeed.

Such was life. At bottom, if evolution had stuck Reina in a certain niche, such that she lacked a feature to do this or an adaptation for that, then it had trusted her to own and thrive within her lot, grow beyond if her will to survive so dictated. Despite any and all weakness, she had been called to do her best and carry the genus forward—enough said. The only proof she needed were the memories she had of her kids’ first actions in life, when each had been born tail-first and rushed headlong to breach and experience that maiden breath of Jurassic air. She had survived just the same. There was no room for arrogance in the great schema. Only gratitude for her mission, the chance to have embarked on it, could remain.

Reina came back to herself shortly, feeling the sublimation of sadness throughout her form. Her family kept the circle, the quiet swish of waves continuing to fill the cove. Reina hoped that somewhere Cambree was watching them, that in seeing the family come together her soul might have healed too.

Afterward, since for the herd’s safety Reina had to bleed out alone, the family came to goodbyes, inducing no less than heartbreak in everyone involved. Brushes and gazes between them transpired in utmost silence, broken only by Reina as she told her family her thoughts. The children received all of her love and encouragement, her thanks and apologies for this the story of their lives. Sever ought to have confidence in himself; he was more talented than he knew. Nomi should mind unnecessary movements; she would artfully catch twice as many squid. And Nubar had to think like a cephalopod; his tactical intelligence would climb to the sky. Despite her own tranquility, Reina could only say or do so much for them now, and it still tortured her to exist inside herself and witness this truth. She gave Euram the same grace and affection, then brought him close and lightly nipped his face. The adults spoke alone to finish, Reina delineating her last wishes and sharing any knowledge she had kept private up to now, all her strategies laid bare. Euram had no living relatives. He promised he would find others in the herd, a female interested in learning the family tricks. Reina named a few friends and smiled. He would need help raising the kids, plenty of help trying to get over her.

“Protect them, Euram,” she said. “Great One be with.”

That night, Reina remained by herself in the cove, having watched the Great One pass and plunge down in the west, its eye return as the moon hunting in blackness. She swore she could still hear the sun dance and its flowing, subtle sough. The shallows about her sung with blood, and she felt she was fading fast. Without a thought, for she had been thinking all evening as to where to meet her end, she took the utmost breath and dove under, making for the deep. From the surface light ceased to exist, so perfect was the dark. Reina could pull from its simple medium nothing with her gaze, and thereby she saw it weave the contents of delusion. Her family appeared to her in the midst of another sun dance, but this time they occupied the center, the eye, the source, themselves ringed by the entirety of the herd. Reina knew she was seeing things especially because this very rite for her was slated to commence later in the day. Yet she couldn’t help but swim into the magic, watching her loves breach toward the noontide in celebration of her life. Euram and the kids sprung one after the other, chasing legends down.

Reina arrived at the sea bottom and traveled a soft decline out to the sandy floor. She found the water deserted, the ammonites having risen to surface-feed, leaving just her in a void with the benthos. Reina drifted through with her head low, adoration high. Here crinoids bloomed, sea stars stretched, and abundant oysters stippled the terrain. This spot Sever had shown her beneath the diving column, and how she had scorned it at first! But quiet beauty it was, and now the mother ophthalmosaur stopped to smell the sea lilies at last.

Buoyant brontosaurs, did they smell good.

Reina meandered, acquainting herself with the scents and sights she’d missed. Tickled sighs she gave back, some followed by the tiniest whimper. By the showy benthic organisms she distracted herself till she could distract herself no longer.

Then Reina noticed the moon. It was off over the meadow and in the water, a stark whiteness the size of Nubar staring her down. She had seen the bright hunter in the sky already, so she wondered just what this eidolon was doing here, messing with her failing vision. Right away it began to creep forward, bearing down on her from above. It looked like the eye of a blind, ponderous animal. Reina felt the eye-moon was hardly blind though, that it knew well why it loomed over her with the impression of predatory sentience one creature easily recognized in another.

She saw jet-black jaws, teeth bladed and carved out of primordial nightmare, just about come into being from the greater darkness, such that along with the eye-moon they composed the head of a monstrous ichthyosaur when it was viewed from the side. Reina trembled.

Then, her energy spent, blood drained, heart winding down, she limped her way over to the beast.

The Great One turned its ebon rostrum and opened wide.

Reina came willingly.

The jaws came down and brought her into the deep.

Member discussion